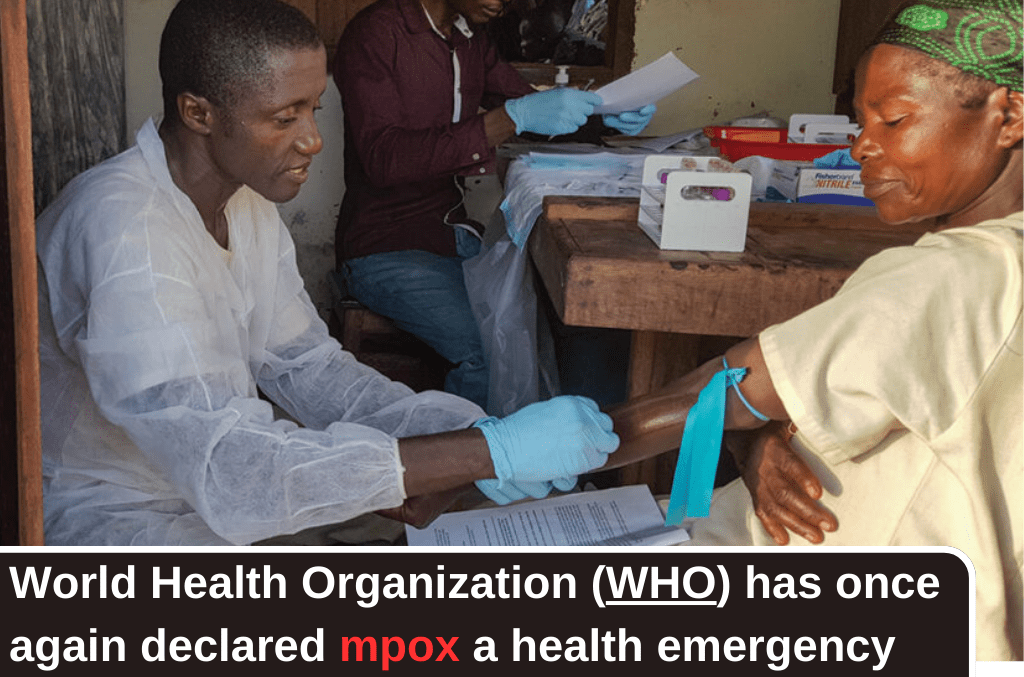

The World Health Organization (WHO) has once again declared mpox formerly known as monkeypox a public health emergency of international concern. This announcement is in response to a new variant of the virus that has emerged in Central and West Africa and is now making its way beyond the continent, with the first known case outside Africa recently reported in Sweden.

The recent detection of a new mpox variant in Sweden marks a significant and concerning development. The virus, which has been wreaking havoc in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and other parts of Africa, has now crossed borders, raising fears of a wider global spread.

On August 15, Swedish health officials confirmed that an individual who had traveled to an affected area was infected with this new strain of mpox, signaling the virus’s potential to spread beyond Africa.

This outbreak in Sweden is the first instance of the virus being detected outside Africa and has prompted health authorities across Europe to heighten their vigilance. The European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) has warned that more cases may be inevitable due to frequent travel between Europe and Africa. In response, European countries are increasing their preparedness, issuing travel advisories, and urging travelers to assess their vaccination status before visiting affected areas.

The Crisis in Africa

The mpox outbreak in Africa is particularly dire, with the virus spreading rapidly across several countries. The Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) reported on August 13, 2024, that there have been over 17,000 suspected cases across the continent this year. Tragically, at least 517 people have lost their lives to the disease, with the majority of cases and deaths occurring in the DRC.

The situation in the DRC is dire. With 15,664 reported cases and 537 deaths, the outbreak has already surpassed the totals seen in 2023, highlighting the escalating nature of the crisis. The country’s healthcare system, already under immense strain from other public health challenges such as malnutrition, cholera, and measles, is struggling to cope with the additional burden of mpox.

The outbreak has disproportionately affected children, who are among the most vulnerable. In some regions of the DRC, children under the age of 15 account for nearly 70% of suspected cases. This is a troubling trend, as children were not as severely impacted during the 2022-2023 global mpox outbreak.

Understanding Mpox: What is mpox?

Mpox is an infectious disease caused by a virus from the same family as smallpox. The virus is primarily found in Central and West Africa, where it spreads among animals such as rodents and monkeys. However, it occasionally jumps to humans, causing outbreaks. The disease can manifest in symptoms such as a rash, skin lesions, fever, headache, and swollen lymph nodes.

There are two distinct lineages of mpox: clade I and clade II. Clade I, which is driving the current outbreak, is associated with more severe disease and a higher risk of death, particularly among children, pregnant women, and those with weakened immune systems. The global mpox outbreak in 2022 and 2023 was primarily caused by clade II, a less severe strain. The current outbreak is being driven by a subtype of clade I, known as clade Ib, which is particularly fatal.

© CDC Monkeypox, a virus first discovered in monkeys in 1958 and that spread to humans in 1970, is now being seen in small but rising numbers in Western Europe and North America.

Transmission and Spread: How does mpox spread?

Mpox spreads primarily through close contact with an infected person or animal. The virus can be transmitted through skin-to-skin contact, sexual contact, kissing, or touching contaminated objects such as bedding, towels, or linens. In the current outbreak, sexual transmission has been identified as a significant factor, particularly among men who have sex with men and sex workers in certain regions of Africa, including the South Kivu province of the DRC.

The virus can also be spread through respiratory droplets during close face-to-face contact, although this mode of transmission is less common. People remain infectious until all their sores have healed, and it is crucial to avoid scratching sores to prevent further spread and secondary infections.

The WHO’s latest situation report, published on August 12, 2024, emphasizes that while sexual contact is a key transmission route, other factors, including poor surveillance and stigma around sexual transmission, make it difficult to fully understand the virus’s spread.

Animals also play a role in the transmission of mpox. The virus can spread from animals to humans through bites, scratches, or contact with body fluids. Hunting, handling, or consuming infected animals can also lead to human infection, particularly in regions where such practices are common.

What Are the Symptoms of Mpox?

According to Mayoclinic, The earliest sign of mpox often appears as a rash, starting as flat, red sores that gradually evolve into blisters. These blisters can be itchy or painful and usually begin on the face before spreading to other parts of the body, including the hands and feet. Additionally, the rash may extend to the mouth, genitals, or anus, forming painful lesions.

The progression of the rash and blisters typically spans two to four weeks. During this time, patients may experience a range of other symptoms, such as fever, headaches, muscle pain, backache, extreme fatigue, and swollen lymph nodes. Symptoms generally manifest within the first week of infection but can appear anywhere from one day to three weeks after exposure. Notably, some individuals may carry and spread the virus without showing any symptoms, which complicates efforts to control the spread of the disease.

Treatment: How is mpox treated?

Treatment for mpox primarily involves managing symptoms and preventing complications. Supportive care, including pain relief, hydration, and treating secondary infections, is the cornerstone of mpox treatment. However, specific antiviral treatments are limited. Tecovirimat, an antiviral drug that was used during the 2022-2023 mpox outbreak, has recently been found ineffective against the clade I virus currently driving the emergency outbreak.

Vaccination: is there an mpox vaccine?

Vaccination remains the most effective preventive measure against mpox. The mpox vaccine, which requires two doses for full protection, is recommended for individuals at high risk of exposure, particularly those in affected areas or with potential contact with the virus. Smallpox vaccines have also been shown to provide some protection against mpox, but it is unclear how effective these vaccines will be against the new variant.

Unfortunately, vaccine availability is a significant issue, particularly in Africa. Despite the high demand, with an estimated need of 10 million doses across the continent, many African countries have minimal to no vaccine supplies. The DRC, which requested 4 million vaccine doses, has yet to receive any, highlighting the stark disparity in global health responses. This lack of access to vaccines and treatments has left vulnerable populations in Africa at heightened risk, exacerbating the ongoing crisis.

How this Outbreak Different From 2022 Outbreak?

The current mpox outbreak differs significantly from the 2022 outbreak in both scale and severity. While the 2022 outbreak, driven by clade II, was largely contained within months due to effective vaccination programs and public health measures, the situation in 2024 is more complex. The clade I virus responsible for the current outbreak is more virulent and has caused more severe illness, particularly in children.

The outbreak has spread to new regions within Africa, including Kenya, Rwanda, Burundi, and Uganda—countries that had previously not reported mpox cases. This expansion into new territories indicates the virus’s growing reach and the potential for further spread if the outbreak is not contained.

What Is the Survival Rate for Mpox?

The survival rate for mpox varies significantly depending on the virus strain. For those infected with the clade II strain, the prognosis is generally favorable, with over 99.9% of patients recovering from the illness. However, the situation is more concerning for individuals infected with clade I, where the mortality rate can reach up to 10%. This higher risk is particularly pronounced in vulnerable groups, including children, pregnant women, and those with compromised immune systems.

Who Is at Risk?

The populations most at risk in the current outbreak are those who have not been vaccinated against smallpox. Smallpox vaccination was discontinued after the disease was declared eradicated in 1980, leaving a large portion of the global population susceptible to mpox. This includes younger generations who have never received the smallpox vaccine.

Children are particularly vulnerable in the current outbreak, with a significant proportion of cases and deaths occurring in those under the age of five. Pregnant women, immunocompromised individuals, and people with underlying health conditions are also at higher risk of severe disease.

In June, the WHO reported that, in the DRC, 39 percent of cases and 62 percent of deaths were in children under 5 years old.

How Quickly Will These Mpox Outbreaks Be Stopped?

The timeline for controlling the current mpox outbreaks remains uncertain. The 2022 outbreak was slowed within months due to swift public health interventions, including vaccination campaigns in wealthy countries. However, the situation in Africa is more challenging, given the limited access to vaccines and healthcare resources.

The majority of mpox cases are currently concentrated in Africa, with 96% of reported cases and deaths occurring in the DRC. The country’s healthcare system, already overwhelmed by other public health crises, is struggling to manage the additional burden of mpox. Without significant international support, including the provision of vaccines and medical supplies, it is unlikely that the outbreak will be contained in the near future.

Investing in the global response to mpox, particularly in Africa, is not only a moral imperative but also a strategic necessity. Containing the outbreak at its source will prevent further spread and reduce the risk of the virus reaching other parts of the world.